Why are Dental Professionals, Educators and Meeting Planners NOT Curious?

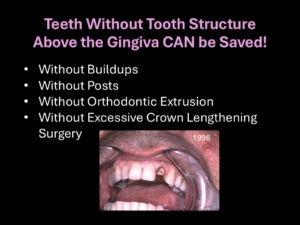

Recently I created a 5-minute video: “Teeth without Tooth Structure Above the Gingiva Can Be Saved.” [View the video here: https://youtu.be/T2Y7Q7l7wFk] The title slide states emphatically that this feat can be done without posts, buildups, orthodontic extrusion or extensive periodontal crown lengthening.

Recently I created a 5-minute video: “Teeth without Tooth Structure Above the Gingiva Can Be Saved.” [View the video here: https://youtu.be/T2Y7Q7l7wFk] The title slide states emphatically that this feat can be done without posts, buildups, orthodontic extrusion or extensive periodontal crown lengthening.

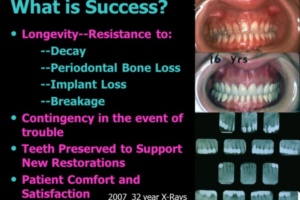

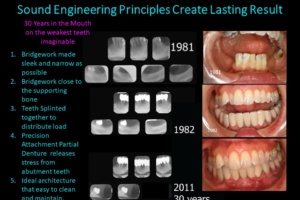

Saving teeth flush with the gingiva without buildups or posts is a feat that most restorative dentists consider impossible. This feat certainly cannot be accomplished with fancy chairside digital milling machines. As a result, a high percentage of dentists extract these teeth. They either do not know how to save them or they would rather not save them so that they can place implants. Most dentists have poor crown and bridge skills because much of what they have been taught is incorrect and based on misconceptions. I have 70 years of documented evidence to support this statement.

I sent the video to nearly 3000 individuals, including representatives of dental schools, meeting planners from continuing education venues and influential members of the dental profession. The video was also posted several times on social media.

Clearly the video, along with its title, is designed to be provocative. One would logically assume that a provocative video would spark great interest. But sadly, that is not the case. Why is the dental profession not the least bit curious to learn how the “impossible” can be made possible? Saving teeth with no clinical crowns would enable dentists to treat patients that they are currently turning away. The ability to save these teeth also opens the door for patient treatment options that they have never considered.

One reason for the lack of curiosity could be that maintaining the status quo is comfortable and familiar. It is quite lucrative to extract teeth and place implants. Most dentists don’t value excellence in crown and bridge techniques. They fail to understand that patients visit them because they want to save their own teeth, not to have extractions and implants. Implants should be a last resort, except in certain circumstances. Patients want dentists to be proficient in crown and bridgework procedures as well as with implant techniques so that they can choose the treatment option that is truly best for them. But patients are being short-changed because they are rarely given choices.

One reason for the lack of curiosity could be that maintaining the status quo is comfortable and familiar. It is quite lucrative to extract teeth and place implants. Most dentists don’t value excellence in crown and bridge techniques. They fail to understand that patients visit them because they want to save their own teeth, not to have extractions and implants. Implants should be a last resort, except in certain circumstances. Patients want dentists to be proficient in crown and bridgework procedures as well as with implant techniques so that they can choose the treatment option that is truly best for them. But patients are being short-changed because they are rarely given choices.

When I started my career, my colleagues and I were eager to learn anything that could help us become better dentists. I still have a voracious appetite for learning anything that could make me a better practitioner. My father was my role model and mentor, and he was the best dental practitioner I ever knew. He was way ahead of his time and was revered in his day. Early in his career he vowed to become the very best dentist, and he worked hard to make that intention a reality. Despite all the new, fancy technology and materials, I have not met anyone who could match the sheer volume and quality of work that he accomplished during his lifetime. And I have the pictures to prove it!

These days I rarely hear anyone making these vows. It seems to me that—to most dentists, educators and meeting planners–evidence does not matter, science does not matter, and merit does not matter. What does matter? Economics, popularity, and workflow. Success in Dentistry is today measured by affluence rather than by excellence. The founding fathers of full coverage restorative dentistry would be horrified to learn what became of the profession that they created and so dearly loved. But what worries me most is the overall lack of curiosity.

These days I rarely hear anyone making these vows. It seems to me that—to most dentists, educators and meeting planners–evidence does not matter, science does not matter, and merit does not matter. What does matter? Economics, popularity, and workflow. Success in Dentistry is today measured by affluence rather than by excellence. The founding fathers of full coverage restorative dentistry would be horrified to learn what became of the profession that they created and so dearly loved. But what worries me most is the overall lack of curiosity.

Drs. Eli Adashi, Abdeul-Kareem Ahmed and Philip Gruppuso, emphatically state in their American Journal of Medicine article1 that “no other attribute could underlie the powers of observation that frame a working hypothesis, now called a diagnosis. No other habit of mind could serve as the starting point . . . to comprehend and to master the abnormal.” Curiosity, the authors explain, is “the driving force behind the progress of science.” It is logical to expect curiosity to fuel the advancement of any scientific and learned profession such as Dentistry.

Andrew Miligan, Education Project and Research Coordinator for The Right Question Institute, believes that students must develop a mindset of curiosity to advance the development of four other critically important “C”s within their formal education: creativity, critical thinking, communication, and collaboration. Curiosity is the launchpad for students to ask the right questions—and to care enough to actually ask them2.

If formal education were really effective, the majority of professionals should be brimming with all five “C”s, especially “curiosity.” “It is a profound enigma,” says Dominick Branchaud in his article The Paradox of Curiosity: Why People Stopped Wondering; “that the flames of curiosity in many individuals flicker with the faintest glow.” He points out that people are today so connected to the marvels of engineering in their daily routines that they scarcely reflect on how they function. “It’s as though the magic of technology has become so normalized that it no longer inspires wonder,” he explains. The answers are so accessible that “the act of seeking them out has lost its allure.” Every day to the un-curious is a repeat of the previous day, so “the unknown is less of a mystery to solve and more of an inconvenience to avoid.”

The decline of curiosity, notes Branchaud, has led to intellectual stagnation, where learning is limited and personal development is stunted. Branchaud says that uncurious individuals are trapped in the “echo chambers of their own beliefs and knowledge.” They cannot see beyond their current understanding to consider different perspectives. Stagnation not only limits individual potential, it impoverishes intellectual diversity within the entire professional community as well.

The decline of curiosity, notes Branchaud, has led to intellectual stagnation, where learning is limited and personal development is stunted. Branchaud says that uncurious individuals are trapped in the “echo chambers of their own beliefs and knowledge.” They cannot see beyond their current understanding to consider different perspectives. Stagnation not only limits individual potential, it impoverishes intellectual diversity within the entire professional community as well.

How can we reignite curiosity among dental professionals? How do we cultivate a mindset of wonder? Branchaud believes that the answers lie in shifting perspective so that we no longer view the world as a collection of facts and figures, but as a universe teeming with mysteries for us to discover. Every individual patient and every restorative problem has a story that reveals secrets, and surprises that inspire. Branchaud says that “by adopting a mindset of wonder, we transform our interaction with the world from one of passive consumption to active engagement.”

Encouraging a curiosity mindset begins with simple questions such as “How” and “Why.” These questions compel us to examine what is beyond the surface. Curiosity is not just about finding answers, it’s about learning to appreciate and enjoy the pursuit of learning. It is about learning for the sake of learning and not for the sake of fulfilling requirements, achieving a degree, or the ability to make a quick buck from patients.

Encouraging a curiosity mindset begins with simple questions such as “How” and “Why.” These questions compel us to examine what is beyond the surface. Curiosity is not just about finding answers, it’s about learning to appreciate and enjoy the pursuit of learning. It is about learning for the sake of learning and not for the sake of fulfilling requirements, achieving a degree, or the ability to make a quick buck from patients.

To make learning a lifelong quest, the profession must create an environment that supports and encourages curiosity. Educators must be open to exposing students to new paradigms that may challenge their own belief systems. Researchers must make science a priority so that they conduct research for the sake of furthering scientific knowledge rather than for the sake of fulfilling a corporate or personal agenda. Meeting planners must seek to create balanced curricula, and not choose speakers based on popularity or whether they bring funding through corporate sponsorship.

Perhaps the best course of action is to start with the newest generation. In the Old Testament, the Israelites were forced to wander the desert for 40 years before they could enter the promised land to ensure that every soul that grew up in Egypt died off. The people of the old generation were so ingrained with a slave mentality that they could not embrace freedom. The promised land could only be attained with a “freedom” mindset.

I have noticed that aspiring professionals of the newest generation begin their education with curiosity, a thirst for learning, and a refreshing idealism. But somewhere during their career journey they shed these traits and succumb to a slave mentality. They lose their idealism, settling for mediocrity to chase a buck. Providing the highest quality care to patients–once their major priority–becomes relegated to the back burner. Clearly, we must change this dynamic If we are serious about improving the quality of patient care and leading the profession to new heights.

I have noticed that aspiring professionals of the newest generation begin their education with curiosity, a thirst for learning, and a refreshing idealism. But somewhere during their career journey they shed these traits and succumb to a slave mentality. They lose their idealism, settling for mediocrity to chase a buck. Providing the highest quality care to patients–once their major priority–becomes relegated to the back burner. Clearly, we must change this dynamic If we are serious about improving the quality of patient care and leading the profession to new heights.

Branchaud sums up perfectly what we must do:

“As we stand at the crossroads of the present and the future, the call to reignite curiosity is more urgent than ever. It is a call that demands action from each of us — educators, leaders, parents, policymakers, and individuals. We must all play our part in creating a culture that values and nurtures curiosity, recognizing it as the driving force behind personal fulfillment, innovation, and societal progress.”

1Eli Y. Adashi, MD, MSa, Abdul-Kareem H. Ahmed, SM, MDb, Philip A. Gruppuso, MDa; “The Importance of Being Curious;” The American Journal of Medicine, Vol 132, No 6, June 2019; p.673-674; https://www.amjmed.com/article/S0002-9343(18)31174-4/fulltext.

2Miligan, Andrew; Edweek; May 24, 2017; https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/opinion-the-importance-of-curiosity-and-questions-in-21st-century-learning/2017/05.

3 Branchaud, Dominic; “The Paradox of Curiosity: Why People Stopped Wondering;” April 20, 2024; https://medium.com/@genuinemeaningfulness/the-paradox-of-curiosity-why-people-stopped-wondering-924c47460201; Originally published at https://meaningfulness.com.au