Disturbing Trends in Dental Manufacturing

I remember a time when the major dental manufacturing companies were actually interested in furthering the practice of Dentistry. We–dentists who want to deliver the highest quality care to patients–need the right tools to do so. We depend on dental manufacturing companies to help us in this endeavor. Dental manufacturing companies do not see patients and they have no idea how their products actually work and hold up in the mouth. They do know what tools the average practitioner is willing to settle for. At one time most dental manufacturing companies tried to accommodate all types of practitioners.

Most dental manufacturers at the beginning of my career were eager to collaborate with dentists in order to offer products for the practice of high-quality dentistry. Often these products were innovative advancements for the profession. No more. Ideas of planned obsolescence and bottom-line thinking now rule the marketplace.

I have seen sweeping changes in attitude by dental manufacturers since I started in practice over 45 years ago. I was trained by a master and pioneer in full mouth reconstruction and crown and bridge dentistry—my father. He was renowned during his lifetime and well respected by his peers. I remember the great relationship we had with representatives from the dental manufacturing world. They often sent their top technicians to collaborate with us. We had actual proof of efficacy of their products essential to creating ideal dentistry and this proof was of great interest to them.

But today, many of these products have been discontinued. Never mind proof of efficacy. All that matters today is how they sell. Never during the course of my career did I ever think that basic products necessary for ideal dentistry would go by the wayside and that I would have to scramble for alternatives that could accomplish the same tasks.

The common denominator is that no matter how hard one pleads with manufacturing companies not to discontinue important products; no matter what proof of efficacy is sent to them, they adamantly refuse to reinstate those products or figure out a way that they can be made more profitably. It matters not a whit to them how these products benefit patient care. In interacting with these companies, I found out that it is not uncommon to be treated with indifference or downright rudeness.

Since moving to Arizona, I have had to spend a great deal of my time finding replacements for many standard or excellent products, something I thought I would never have to do. Fortunately, I have been able to come up with substitutes for some of them. While these substitutes are generally adequate—they are usually not better.

Here are several examples of bygone products that were important advancements for the practice of high-quality dentistry. I don’t want to mention the names of the companies for obvious reasons—I simply want to expose the patterns and trends that I am seeing.

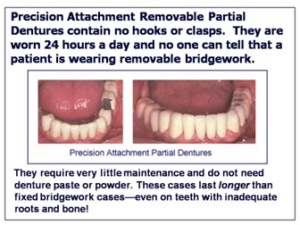

The Passive Precision Attachment

The passive precision attachment comes from the very roots of full coverage restorative dentistry. Only one design offers truly passive function for the removable partial denture, and it consists of a simple male-female. All of the other designs currently on the market are locking or gripping mechanisms that inflict deleterious forces on the abutment teeth. In this regard they function no better than clasps, which grip the abutment teeth and torque them until they are eventually lost. Clasp and locking attachment partials are really transitory restorations to a denture.

The passive precision attachment comes from the very roots of full coverage restorative dentistry. Only one design offers truly passive function for the removable partial denture, and it consists of a simple male-female. All of the other designs currently on the market are locking or gripping mechanisms that inflict deleterious forces on the abutment teeth. In this regard they function no better than clasps, which grip the abutment teeth and torque them until they are eventually lost. Clasp and locking attachment partials are really transitory restorations to a denture.

However, the simple male-female attachment is the only design that does not grip or lock the abutment teeth for retention. The means of retention is the path of insertion, which is tilted in two directions. This path of insertion/withdrawal is different than the direction of muscle contraction and gravity. As a result, this arrangement dissipates stress: the partial denture can move slightly to release the stress, but it cannot be dislodged.

The concept of the passive precision attachment and double-tilt path of insertion was first introduced in 1906 by Dr. Herman Chayes. In 1921, a well-known dental manufacturing company patented its own design in 1921. My father compiled about a dozen cases (pictures and X-Rays) into a report for this company to demonstrate the attachment’s efficacy and longevity for FDA approval. I have all the pictures. I also have supporting documentation for this attachment that spans 70 years, and it is compiled into a textbook that I wrote that is available on Amazon.com: The Double Tilt Precision Attachment Case for Natural Teeth and Implants. (https://www.amazon.com/s?k=Books+by+Edward+Feinberg+DMD&ref=cs_503_search) The attachment has a 100 year track record for use with natural tooth abutments and a 25 year track record to use with implant abutments.

The company that made the original attachment is under different management today than at the beginning of my career. The new management does not care about their company’s amazing history of its own passive precision attachment! Perhaps company leaders concluded that the attachments were too difficult for the vast majority of dentists to learn how to use. The use of these attachments is, after all, only for ideal full coverage restorative dentistry.

There is another reason that makes much more sense. This company hired a chief technician that invented his own attachment that grips the abutment teeth with vinyl sleeves. This attachment does not have the track record for longevity that their original attachment has. The components of their original attachment rarely require replacement, even after decades of continuous 24-hour-a-day wear. By contrast, the vinyl sleeves on the attachment this company is heavily promoting do not last long and require continual replacement. Perhaps the company is only interested in selling that particular attachment because dentists will require an endless supply of vinyl sleeves.

The company’s chief technician is not interested in having his company promote any other attachment but his own. I know this to be true because I interacted with him in the past. After extensive discussions with him, I sent him all of the information and supporting documentation for the passive male-female attachment that came from his company’s roots. I never heard from him again.

Other companies have manufactured male-female attachments that have proven successful with precision attachment cases. However, no company exists at the present time that offers a simple male-female attachment for precision attachment partial denture cases! The only solution at present is to have the attachments custom cast. The Creodent lab in Manhattan has developed computer-generated patterns that can be 3D printed in burnout acrylic that is then cast with a Ceramicor-like alloy. There are other manufacturers that may also be able to provide attachments in this manner.

All attachments to this point in history have been cast, usually with special molds for interchangeable parts. Eventually the molds wear out and apparently creating new molds requires substantial investment. In the future, it may be possible to have the attachments milled, instead of cast. Milling circumvents many of the problems inherent in casting, and milled restorations may actually be more accurate than castings. The Strategy Milling© Company of Pittsburgh, which is at the forefront of milling precious metals, has been investigating a solution. Apparently, there are some technical problems that have yet to be solved before the attachments can be milled.

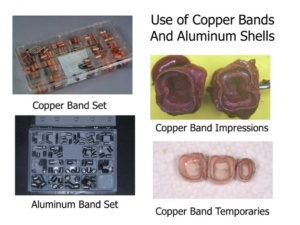

The Copper Band

Copper Bands have been around since the beginning of full coverage restorative dentistry. This year, manufacturers stopped making the copper bands. There are still some suppliers who have copper bands and no doubt there are “old timers” who would be happy to donate their copper bands to a younger practitioner.

Copper Bands have been around since the beginning of full coverage restorative dentistry. This year, manufacturers stopped making the copper bands. There are still some suppliers who have copper bands and no doubt there are “old timers” who would be happy to donate their copper bands to a younger practitioner.

Copper bands are used for two purposes. The first purpose is for registering an impression of the entire root surface below the gingiva. There is no other way to accomplish this task without cutting away the gingiva and no practitioner is going to do that. The standard retraction cord technique cannot register an impression of the entire root surface below the gingiva.

The copper band impression is the standard by which all other techniques should be compared. It has by far the best track record. I have proof–70 years of documented cases where all of the dentistry was fabricated with copper bands. But today’s practitioners don’t even know about the standard that came from Dentistry’s roots. Because they are poorly educated, they consider copper bands “old-fashioned.” There is also an indoctrinated misconception that this type of impression can do harm by impinging on the gingival attachment. This idea is false.

Copper bands are also used to create retentive temporaries on teeth with little or no clinical crowns. Buildups, posts, orthodontic extrusion, or extensive crown lengthening procedures are not necessary for retention when the entire root surface under the gingiva is used for retention. Today’s practitioners are so indoctrinated in post and buildup fabrication (and the resulting insurance income) that they refuse to recognize that a different approach would negate their use altogether. Posts and buildups often fail and can, in fact, cause loss of teeth.

Copper bands can be used to establish a firm grip on the root surface for temporary restorations. Copper band temporaries have superior fit and retention and fit like permanent restorations fabricated with copper band impressions. Their use markedly reduces patient visits for re-cementation of provisional restorations. Like permanent restorations, copper band temporaries are modeled on the Mason Jar cover, which is the best-known means of food preservation, so recurrent decay is a rarity. Copper itself is extremely antibacterial and studies have shown that copper has zero bacteria on its surface, unlike stainless steel and other metals. I have had patients actually wear copper band provisional restorations for years and the preparations remained pristine underneath.

Although several dental manufacturers actually have the machines that can fabricate copper bands, they are reluctant to make them—even for a custom order. They only want to make 10,000 of each size at a time, because the machine has to be calibrated to fabricate each size. One manufacturer told me that he would have to charge me $10 per band to make it cost-effective for him to make them. Of course, this cost is not reasonable.

Fortunately, aluminum shells are widely available from several dental supply companies. Aluminum shells are manufactured in the exact same sizes as copper bands and will fit perfectly on holders designed for copper bands. Aluminum is not quite as easy to work with as copper, but it does work. Unlike copper bands, aluminum shells are closed off on one end. This end can be easily cut off with a disk, and the cut edges smoothed with a rubber wheel. Like copper bands, aluminum shells may require annealing to soften the metal. However, unlike copper bands, too much heat in the annealing process can cause aluminum shells to burn up.

It is my hope that the dental profession can push the manufacturers to resume making copper bands and make an intensive effort to educate dentists on how to use them effectively.

Renaissance™ Crowns

The Renaissance™ Crowns appeared in the 1980s and were perfectly designed for single crowns. The crowns came in “umbrellas” of gold and palladium foil. Renaissance™ crowns combined the best of two worlds: the beauty of the ceramic material and the superior fit, retention and protection against decay afforded by porcelain-to-metal restorations.

The Renaissance™ Crowns appeared in the 1980s and were perfectly designed for single crowns. The crowns came in “umbrellas” of gold and palladium foil. Renaissance™ crowns combined the best of two worlds: the beauty of the ceramic material and the superior fit, retention and protection against decay afforded by porcelain-to-metal restorations.

Renaissance™ crowns were much thinner than cast alloys. Renaissance™ crowns utilized a direct technique, meaning they were made directly on the original dies. A direct technique is less likely to incorporate error than an indirect technique such as cast restorations, which require the creation of a wax-up, investment, burnout, and casting.

Renaissance™ crowns could be fabricated in twenty minutes, ready to bake porcelain. They were so easy to make that they could easily be made in the office. The technique consisted of closing the umbrella pleats and swaging the umbrella against the die. Excess material beyond the margin was cut away with a scissors. Once the Renaissance™ Crown was adapted tightly to the die, it was briefly heated in an open Bunsen Burner flame so that the gold could melt to solder the umbrella pleats together. My father and I made hundreds of these crowns in the 1980s and 1990s, and they typically lasted for decades with minimal breakage. Apparently, most dentists did not understand how amazing Renaissance™ restorations were and how easy it was to make them. The crowns were also most likely not marketed well.

The replacement for the Renaissance™ crown was the CAPTEK™ crown, which utilizes similar chemistry, but in a different way. Like Renaissance™, CAPTEK™ works well for single crowns and combines the best of the two worlds previously mentioned. The CAPTEK™ crowns are much stronger than the Renaissance™ Crowns, as they cannot be easily bent. However, unlike a Renaissance™ Crown, CAPTEK™ is an indirect technique in that a duplicate refractory die has to be made from the original die in order to create the CAPTEK™ crowns. Wax-impregnated palladium sheets are adapted to the refractory die and heated in an oven for a half hour; then wax-impregnated gold sheets are applied and heated again in the oven for a half hour. The entire process requires the use of substantially more materials than the Renaissance process, and fabrication takes up a whole afternoon. My technician loved to make Renaissance™ crowns but hated to make the CAPTEK™ crowns. Unlike Renaissance™ crowns, which were discontinued long ago, CAPTEK™ crowns are still available.

One of the problems with products and materials in general is that they are often stretched beyond their limitations and both the manufacturers of Renaissance™ and CAPTEK™ were guilty of this practice. Both manufacturers provided tricky protocols to connect crowns and pontics in order to fabricate bridgework. It was clear from the get-go that these products were best suited for single crowns.

I believe digital dentistry, along with milling and 3D printing, may come up with better solutions in the future. The main advantages of Renaissance™ crowns were ease of fabrication and superior fit. They fit like porcelain-to-metal restorations with protection against decay and superior retention. Within 20 minutes Renaissance™ crowns could be fabricated and ready for porcelain application. Renaissance crowns™ had a long track record of longevity with very little breakage. They were a very good alternative to all-ceramic crowns because they not only allowed for maximum esthetics, they provided protection against recurrent decay and superior retention.

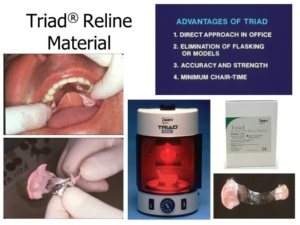

Triad™ Composite Materials

Triad™ is the latest fantastic product to go by the wayside. It was perhaps the best reline material ever invented. It was easy to use, not messy and gave the operator maximum control over the outcome. The composite material was innocuous and came in sheets that had to be protected from ambient light.

Triad™ is the latest fantastic product to go by the wayside. It was perhaps the best reline material ever invented. It was easy to use, not messy and gave the operator maximum control over the outcome. The composite material was innocuous and came in sheets that had to be protected from ambient light.

Relining partials and dentures can be tricky, and it is not uncommon to make a mistake requiring the tedious removal and replacement of the reline material. After removing some of the inside of a denture, triad material could be added a little at a time to allow maximum flow and conform to the patient’s tissues. Excess material was easily removed with a Bard-Parker knife and there was no gloppy mess, as with most chairside reline materials. The Triad™ material was ideal for border molding and could be pre-solidified in the mouth with the curing light. When the operator was satisfied with fit and flow of the reline material, the denture was placed in the Triad™ light curing oven for final cure. Once hardened, the Triad™ material proved to be quite durable and stain resistant.

The Triad™ material was ideal for relining precision attachment cases, which can be difficult to reline. The attachments and palatal/lingual bars must be completely inserted to the “home” position when relining these cases—without the patient occluding on the removable partial denture. Otherwise, the reline could result in excess thickness, food-trapping space under the bar, or poor fit, tissue inflammation, and discomfort.

The Triad™ material allowed the operator an unlimited amount of working time to ensure a perfect result. Curing takes place outside of the mouth so there is no chance of reline material setting within the attachment system. By contrast, conventional reline materials are messy to work with and have limited working time. They are usually allowed to self-cure in the mouth. Disaster can result if excess reline material sets within the attachment system.

Will dental manufacturers allow dentists to offer patients the best products for ideal full coverage restorations in the future?

I believe that the loss of these items is a huge step backward for precision restorative dentistry. The best techniques and materials are NOT always the most popular and may not be the best money-makers for dental manufacturers. Does today’s bottom-line thinking by dental manufacturers mean that dentists will not be able to offer our patients the best treatments in the future that they know how to perform today?

The Dental Profession should be greatly concerned about this disturbing trend. I believe strongly that dental manufacturers should care as much about patient care as we do. It seems to me that they certainly cared a lot more at the beginning of my career than they do now.

What about new and innovative products?

I’m very concerned about new innovative products that could vastly improve the practice of ideal dentistry in the future coming to the marketplace. Will dental manufacturers be willing to take risks inherent in investing in new products? Perhaps not. In fact, in some cases they have already shown that they are unwilling.

I’m very concerned about new innovative products that could vastly improve the practice of ideal dentistry in the future coming to the marketplace. Will dental manufacturers be willing to take risks inherent in investing in new products? Perhaps not. In fact, in some cases they have already shown that they are unwilling.

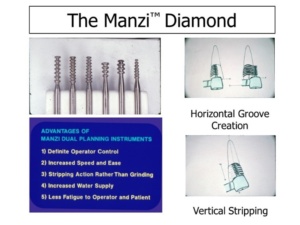

There was a brilliant practitioner—Dr. Walter Manzi—who practiced dentistry in Westchester, NY for many years. He invented and patented an ingenious diamond bur—the Manzi™ Diamond–that could precisely limit the amount of tooth structure that was required to be removed for adequate tooth preparation.

The removal of tooth structure with the Manzi™ Diamond was much faster than the conventional method of wearing away the tooth structure. The diamond consisted of rings of diamonds on a central shaft. When the tooth was prepared with these diamonds, horizontal use of the diamonds created grooves that could only be as deep as the rings, as they were stopped by the central shaft. There were different sizes of Manzi™ diamonds, depending on the desired depth of penetration. When used vertically, grooves were quickly stripped, and the tooth was almost completely prepared. A quick truing-up with a conventional diamond was all that was needed to complete the gross preparation. Such a diamond was not only a great advancement for full coverage preparations but a great advancement for the preparation of veneers, as it would guarantee the removal of just the right amount of tooth structure, and no more.

Dr. Manzi made the diamonds himself and sold them to dentists in kits. My father wrote scholarly articles on the use of these diamonds and snapped a lot of pictures of their use on patients for his courses.

After making the kits for many years, Dr. Manzi decided to meet with several manufacturers who could mass produce and nationally market the diamonds, but he was unsuccessful in procuring an agreement. He continued to manufacture the diamonds himself until he came down with cancer and had to stop. He felt that the chemicals used to make the diamonds contributed to his cancer. “Teach me and let me make them,” I begged him. I would have gladly made them for him for nothing. But he refused. “You don’t know what you’re asking,” he replied.

After Dr. Manzi passed away and his patent ran out, I took some of the diamonds and along with my father’s articles to several manufacturers. I, too, was unsuccessful in finding a company that was willing to manufacture the diamonds. Perhaps the manufacturing process was too complex—I had the feeling that the manufacturers may not have understood how those diamonds were actually made. Perhaps they did not think the diamonds would sell. So, here’s the bottom line: no dental professionals have the option to use Manzi™ Diamonds today.

I bet there are many other products with potential value that have failed to inspire manufacturers. Dental manufacturers today only seem interested when products guarantee huge profits. They are not as concerned whether those products actually promote health and stand up to rigorous function in patients. Dental manufacturers do not understand that many of the commonly used techniques used to create full coverage restorations actually violate basic principles that have a proven track record. Equipment and products used for those techniques often fall short and cannot be used for ideal full coverage restorations.

Conclusion

Here is a summary of the disturbing trends I have observed:

- Fewer dental manufacturers appreciate having superior products that support ideal full coverage restorative dentistry–products with a real track record for longevity. They seem unwilling to devote resources to educate dentists on how to use them and would rather discontinue selling them.

- The vast majority of dental manufacturers seem to be perfectly fine with catering to the lowest common denominator. Selling products to meet the bottom line is their ruling consideration. Those products do not have to meet any previously established standard or track record of efficacy—they just have to sell.

- It seems like fewer dental manufacturers are willing to take risks on manufacturing innovative products that may dramatically improve the practice of ideal dentistry but fail to become top sellers.

Dental Manufacturers must be encouraged to change their thinking. They exist primarily to help dentists improve patient care—and they should be willing to collaborate WITH dentists for the benefit of patients. While generating profit is important to the survival of any business, increasing short-term profits should NOT be their primary mission. Dental Manufacturers must be willing to reinstate discontinued products that enhance the practice of dentistry, support dental education, and promote the innovation of new products that conform to basic principles of health and longevity.