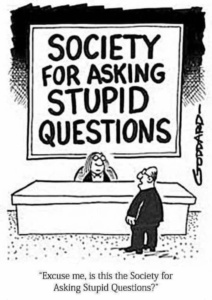

f. Always ask questions. There is an old saying that the only stupid question is the question that has not been asked. Never be afraid that your colleagues will look down on you for asking a “stupid” question. Chances are good that they would like to ask the same question themselves.

f. Always ask questions. There is an old saying that the only stupid question is the question that has not been asked. Never be afraid that your colleagues will look down on you for asking a “stupid” question. Chances are good that they would like to ask the same question themselves.