The Unspoken Conflict of Interest

Several years ago, I was invited to present a course for the ADA’s Annual Session in Orlando, Florida. Before I was allowed to give my presentation, a staff member scrutinized every slide of my presentation to ensure that there were no advertisements or conflicts of interest. Today it is common practice to fill out and sign conflict of interest disclosure form when assuming office in an organization or when giving a presentation at a meeting.

What is a “Conflict-of-Interest?”

The best definition of “conflict-of-interest” that I could find comes from the Cambridge University Press(1):

(1) a situation in which someone cannot make a fair decision because they will be personally affected by the result.

(2) a situation in which someone’s private interests are opposed to that person’s responsibilities to other people:

Apparently, the term “conflict-of-interest” has been in use since at least 1860, so the concept is not new. According to Troy Segal(2), editor and writer for Investopedia, “a conflict-of-interest occurs when an entity or individual becomes unreliable because of a clash between personal interests and professional duties or responsibilities.” When such a situation arises, the party with the conflict of interest is usually asked to remove themselves or can be legally required to recuse themselves. Conflicts of interest can be financial, relational, professional, ideological, time-based or organizational.

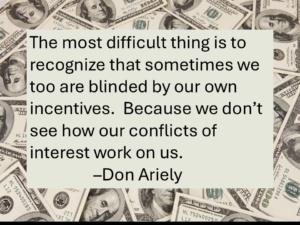

The Elephant in the Room

Conflicts of interest are not always disclosed, and they are often so far under the radar that they are rarely discussed. A major conflict of interest, for example, occurs when healthcare practitioners are torn between providing ideal care for patients and generating business revenue for their practices. But no doctor in his or her right mind would ever sign a conflict-of-interest disclosure form and hand it to a patient. Every doctor wrestles internally between altruism: providing optimal care for the patient—and–egoism: self-serving financial gain. Eli Y. Adashi, MD, MS, in his essay, “Money and Medicine: Indivisible and Irreconcilable(3)” captures perfectly the essence of this battle:

Conflicts of interest are not always disclosed, and they are often so far under the radar that they are rarely discussed. A major conflict of interest, for example, occurs when healthcare practitioners are torn between providing ideal care for patients and generating business revenue for their practices. But no doctor in his or her right mind would ever sign a conflict-of-interest disclosure form and hand it to a patient. Every doctor wrestles internally between altruism: providing optimal care for the patient—and–egoism: self-serving financial gain. Eli Y. Adashi, MD, MS, in his essay, “Money and Medicine: Indivisible and Irreconcilable(3)” captures perfectly the essence of this battle:

“Stripped to its core, medicine [dentistry] is a service industry, the product of which is health care. As such, the practice of medicine [dentistry], not unlike the provision of any other service, is deserving of professional remuneration. Viewed in this light, medicine [dentistry] and money are sensibly interrelated and by extension indivisible. Less clarity exists, however, about the question of whether medicine [dentistry] should be a conduit to wealth accumulation. To its proponents, the notion of medicine[dentistry] as the road to personal wealth constitutes just another example of free-market economics. Medicine [Dentistry], after all, is but another form of business, and conflicts of interest never enter the equation, given a self-regulated, unswerving clinical decision-making process. To its detractors, the notion of self-enrichment from the practice of medicine [dentistry] represents an example of capitalism gone awry. According to this outlook, striving for riches in the healing professions is rife with financial conflicts of interest, with clouded clinical judgments, and with a compromised professional posture. Examined in this light, medicine [dentistry] and money appear irreconcilable.”

For most healthcare professionals, the paradox described by Dr. Adashi is an every day conundrum. “What can I do that is best for the patient? often conflicts with “What can I do to maximize practice revenue?” There are always choices when it comes to providing patient care. Which choice is best? The answer is not always clear-cut. There are no forms to fill out and no Conflict-of-Interest police hawks standing watch.

Conflict of Interest? You be the judge:

Here in Arizona, there is a well-known endodontist who often fills the back cover of magazines with his ad. I had the pleasure of attending his presentation and I discovered that he is an excellent endodontist who does impeccable work. He presented a case that casts a dark shadow on the dentistry-and-money conundrum. The panoramic X-Ray showed that the patient had a good mouth with good long roots and excellent periodontal bone. However, most of the lower posterior teeth had root canals that were obviously done by an amateur, and they were failing. Numerous root canals had to be retreated but the prognosis for successful retreatment was excellent. The presenting doctor wanted to help her so that she could afford the re-treatments. It was clear that I, an expert restorative dentist, could have easily saved all of her teeth. Bridgework properly constructed has an excellent prognosis. I have treated complex restorative cases that have lasted in health for over 40 years with few changes in follow-up X-Rays. I would gladly have helped that patient afford her bridgework.

Here in Arizona, there is a well-known endodontist who often fills the back cover of magazines with his ad. I had the pleasure of attending his presentation and I discovered that he is an excellent endodontist who does impeccable work. He presented a case that casts a dark shadow on the dentistry-and-money conundrum. The panoramic X-Ray showed that the patient had a good mouth with good long roots and excellent periodontal bone. However, most of the lower posterior teeth had root canals that were obviously done by an amateur, and they were failing. Numerous root canals had to be retreated but the prognosis for successful retreatment was excellent. The presenting doctor wanted to help her so that she could afford the re-treatments. It was clear that I, an expert restorative dentist, could have easily saved all of her teeth. Bridgework properly constructed has an excellent prognosis. I have treated complex restorative cases that have lasted in health for over 40 years with few changes in follow-up X-Rays. I would gladly have helped that patient afford her bridgework.

The patient, unfortunately, visited another practitioner for a second opinion. That practitioner must have been a super-salesman. He talked her into extracting all of her teeth and placing four implants with an “all-on-four” prosthetic case. The patient was only 23 years old! The patient must have been led to believe that she was getting a quick fix for her dental problems and that—in one visit–all her dental troubles would be forever solved. But nothing could be further from the truth, and it is highly likely that she will one day regret choosing this path. There are several reasons why:

- All-on-Four cases do not have a long track record of longevity. All-on-four cases have not been around that long. The cases are often made with large superstructures that overload the supporting implants and can be difficult to keep clean. Often the supporting implants are immediately loaded, which is an experimental procedure. The conventional approach includes 3-4 months of healing before the implants are loaded with forces. The conventional approach requires the patient to wear a denture during the healing period.

- Contrary to popular belief, implants are not lifetime. I have had implant patients where the implants only lasted 20 years and then they were lost. No one knows why. Usually, these patients were not candidates for new implants afterward. However, when all-on-four cases are placed, the bony ridges are usually flattened. When an all-on-four case fails, it is likely that the patient won’t be able to comfortably wear a denture. Imagine the psychological trauma for a young person with an impaired ability to eat and navigate socially. This type of trauma can be life-destroying.

The all-on-four provider probably collected a nice, lucrative sum for his implant practice. Because there are different treatment options for every dental problem, technically all-on-four treatment is not malpractice. But to me, this highly invasive and drastic treatment option makes my “moral compass” go haywire. I believe that patients should save their own teeth first and that implant therapy should be a last resort, except in certain circumstances. As I result, I feel strongly that in this particular circumstance, implant therapy was not warranted.

The all-on-four provider probably collected a nice, lucrative sum for his implant practice. Because there are different treatment options for every dental problem, technically all-on-four treatment is not malpractice. But to me, this highly invasive and drastic treatment option makes my “moral compass” go haywire. I believe that patients should save their own teeth first and that implant therapy should be a last resort, except in certain circumstances. As I result, I feel strongly that in this particular circumstance, implant therapy was not warranted.

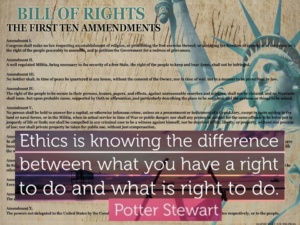

So how do you know whether your moral compass is pointing toward “true north” when treatment planning for a patient?

Here is the test I use when treatment planning for a patient:

If you personally had your patient’s problem, would you choose that treatment for yourself? Would you sit for those procedures and accept all the complications that might arise? Would you recommend such treatment for your loved ones? These questions are the “Golden Rule” of dental treatment—the same rule that is found in both the Old and the New Testaments and in almost all religions: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.”

The best treatment option should be designed to prevent future problems, and contingencies should be included in the event of complications. If one implant fails in an all-on-four case, the entire case is jeopardized and likely to fail. By contrast: if one natural tooth abutment fails under a bridge, it can be extracted without removing or altering the bridgework.

The best treatment option should be designed to prevent future problems, and contingencies should be included in the event of complications. If one implant fails in an all-on-four case, the entire case is jeopardized and likely to fail. By contrast: if one natural tooth abutment fails under a bridge, it can be extracted without removing or altering the bridgework.

As professionals, we are expected to put the best interests of patients first. We are here to serve others, not to take advantage of others for personal gain. I believe that we are obligated to this higher calling despite conflicts that we cannot ignore, such as the pressures of overhead and student loans, along with the lure of financial reward. This is the essence of the Hippocratic Oath; an oath that should be sworn by all healthcare givers. The Oath was rewritten in 1964 by Dr. Louis Lasagna, Academic Dean at Tufts University (my Alma Mater)(4):

The Revised Hippocratic Oath

“I swear to fulfill, to the best of my ability and judgment, this covenant:

“I swear to fulfill, to the best of my ability and judgment, this covenant:

I will respect the hard-won scientific gains of those physicians [dentists] in whose steps I walk and gladly share such knowledge as is mine with those who are to follow.

I will apply, for the benefit of the sick, all measures [that] are required, avoiding those twin traps of overtreatment and therapeutic nihilism.

I will remember that there is art to medicine [dentistry] as well as science, and that warmth, sympathy, and understanding may outweigh the surgeon’s knife or the chemist’s drug.

I will not be ashamed to say, “I know not,” nor will I fail to call in my colleagues when the skills of another are needed for a patient’s recovery.

I will respect the privacy of my patients, for their problems are not disclosed to me that the world may know.

Most especially must I tread with care in matters of life and death. If it is given me to save a life, all thanks. But it may also be within my power to take a life; this awesome responsibility must be faced with great humbleness and awareness of my own frailty.

Above all, I must not play at God.

I will remember that I do not treat a fever chart, a cancerous growth, but a sick human being, whose illness may affect the person’s family and economic stability. My responsibility includes these related problems, if I am to care adequately for the sick.

I will prevent disease whenever I can, for prevention is preferable to cure.

I will remember that I remain a member of society, with special obligations to all my fellow human beings, those sound of mind and body as well as the infirm.

If I do not violate this oath, may I enjoy life and art, respected while I live and remembered with affection thereafter.

May I always act so as to preserve the finest traditions of my calling and may I long experience the joy of healing those who seek my help.”

(1) Cambridge Dictionary, https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/conflict-of-interest

(2) Segal, Troy, “What is a Conflict of Interest?” Investopedia, updated July 30, 2024; Reviewed by Julius Mansa and fact-checked by Vikki Velasquez; https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/conflict-of-interest.asp

(3) Eli Y. Adashi, MD, MS; “Money and Medicine: Indivisible and Irreconcilable;” AMA Journal of Ethics; AMA J Ethics. 2015;17(8):780-786; DOI 10.1001/journalofethics.2015.17.8.msoc1-1508; August, 2015; https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/money-and-medicine-indivisible-and-irreconcilable/2015-08

(4) Dr. Rachita Narsaria, MD; The Procto Blog, March 10, 2015; https://doctors.practo.com/the-hippocratic-oath-the-original-and-revised-version/