On Being a Dental Continuing Education Attendee

Are you easily impressed when you are sitting in an audience of a famous speaker? Are you being taught skills that will directly impact how you practice or are you simply being entertained? Is the speaker really honest about what he or she is presenting?

These are important questions to ask when you are sitting in the classroom. It is important to look more closely at what you are actually seeing and what is actually being said. Don’t be fooled by reputation, status, or fame.

I remember several occasions where I detested what was being presented. On one occasion—at a yearly conference given by the Ninth District Dental Association in NY State, a famous instructor spent all morning showing a roundhouse case that was inserted in two visits. The instructor boasted about the fee he received for doing this case. However, anyone who does precision crown and bridgework knows that a case done this way is not precision dentistry, no matter how beautiful it looks. It is impossible to make a roundhouse case in one piece that actually fits. First, parallelism is almost impossible to achieve for an entire arch of teeth since teeth on one side of the arch are unlikely to be parallel to teeth on the other side of the arch. Second, the materials are not designed to be used in this manner. The manufacturers recommend smaller bridges be made because of dimensional changes that occur from repeatedly heating materials close to their melting points. Full arch splinting can be achieved without making roundhouses. [This subject is discussed in detail in the ONWARD courses.] It is important to realize that just because a bridge “goes on” does not mean it actually “fits.” These are two very different concepts. Bridges that don’t actually fit will be prone to failure and recurrent decay. Sadly, I was the only one in the room who was not impressed. (Scary!)

On another occasion, I was attending a course at the Midwinter Meeting in Chicago with my colleagues Elly Devine and Sam Jacobs. [Both are deceased. The three of us assisted my father, Dr. Elliot Feinberg, with the demonstration courses on live patients that he gave in Scarsdale, NY through the Ninth District Dental Association. My father gave those courses for over 40 years.] There must have been 1000 attendees in this huge auditorium. There were dozens of TVs in the room so that attendees could see up close how a famous instructor was treating a live patient. The instructor prepared a bicuspid for a single crown and proceeded to take the impression. He made it clear that he did not know the depth of the sulcus when he referred to it as the “inner sanctum.” Next, the instructor placed cord into the sulcus so that it completely “disappeared.” The impression was taken with a triple tray with the cord still in place! The sulcus was obviously too deep and was in actuality a pocket! The sulcus should be no more than 3mm in depth. It is also important to take an impression of the entire root surface when making ideal crowns and bridges. [The ONWARD program courses thoroughly explain why.] How can this happen if cord is in the way? I did not see a single attendee express any concern about this procedure—not one whisper!

On another occasion, I was attending a course at the Midwinter Meeting in Chicago with my colleagues Elly Devine and Sam Jacobs. [Both are deceased. The three of us assisted my father, Dr. Elliot Feinberg, with the demonstration courses on live patients that he gave in Scarsdale, NY through the Ninth District Dental Association. My father gave those courses for over 40 years.] There must have been 1000 attendees in this huge auditorium. There were dozens of TVs in the room so that attendees could see up close how a famous instructor was treating a live patient. The instructor prepared a bicuspid for a single crown and proceeded to take the impression. He made it clear that he did not know the depth of the sulcus when he referred to it as the “inner sanctum.” Next, the instructor placed cord into the sulcus so that it completely “disappeared.” The impression was taken with a triple tray with the cord still in place! The sulcus was obviously too deep and was in actuality a pocket! The sulcus should be no more than 3mm in depth. It is also important to take an impression of the entire root surface when making ideal crowns and bridges. [The ONWARD program courses thoroughly explain why.] How can this happen if cord is in the way? I did not see a single attendee express any concern about this procedure—not one whisper!

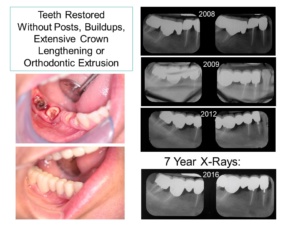

This week I experienced another disturbing episode. I attend study group sessions here in Arizona that are associated with a local institute. There are about ten individuals in the group that includes both generalists and specialists. Typically, we discuss video courses downloaded from the institute. This week, a practitioner showed a case where a lady had an accident as a child and her mouth was restored with a three-unit bridge from the right central incisor to the left lateral incisor that replaced the missing left central incisor. Both of the abutments had root canal therapy and one had a post. Due to changes that occurred, the patient needed new bridgework. There was a substantial discussion about posts and the instructor correctly pointed out the importance of a ferrule in restoring a nonvital tooth. The finished case, however, had no such ferrule and was a butt-joint restoration supported by the post. Can you Imagine this outcome after all that discussion? I pointed out to the group that posts are not necessary, and in fact harmful. [Examples are shown in the adjacent pictures. The ONWARD program covers the restoration of these teeth in great detail.]

That aside, there was absolutely no consideration of engineering principles in the basic design of bridgework. The best scenario for anterior bridgework is to extend the bridgework from canine to canine. The canines have the longest roots and are the cornerstone of the arch. The addition of the canines in the bridgework presented would have given extra support to the nonvital lateral incisor. In addition, if something happened to the lateral incisors, the bridgework could remain without having to remake the entire case.

But the “piece of resistance” was the fact that the opposite lateral was not included in the bridgework but prepared for a veneer instead. Does this make sense? At the very least the bridge should have included both lateral incisors for extra support. What is disturbing is that no one in the room thought there was anything wrong with what was being shown. Apparently, this type of case design is a common scenario. It seems to me that there is a lack of understanding about engineering principles in dentistry. There also seems to be a universal lack of confidence in crown and bridgework skills, as practitioners are reluctant to prepare additional teeth, even to make a stronger case with a better prognosis!

As dentists, we all like to see beautiful dentistry and most instructors do show cases with exquisite porcelain work that are absolutely beautiful. Certainly the case presented in this week’s study group meeting produced a highly esthetic outcome that was a vast improvement over what the patient came in with. But it is critically important to look beyond the surface beauty.

If you take time to notice, most of the cases presented in lectures and in magazine articles are done on healthy individuals with perfect gingiva, and they are usually young people. Almost anything will work on young people, because they have the ability to tolerate cases that are less than ideal. As a patient becomes older; however, tolerance declines, and cases that are less than ideal are more prone to failure.

What about the bulk of patients? Except for practices that specialize in pediatric dentistry, the bulk of patients in most practices are middle-aged and older; many have chronic conditions like diabetes, heart disease and cancer. Some patients were born with weak mouths and have roots that are short, straight and conical. How does the dentistry hold up on these patients? These cases are almost never shown. If the advocated techniques work on these patients, I am all ears. [These are the kinds of cases shown in the ONWARD program. One such example is shown above.]

Most practitioners also show their cases on the day of insertion, when everything looks healthy and beautiful. Attendees are rarely treated to finished X-Rays and post-op X-Rays 5 and 10 years later–even from the most prestigious institutes! Certainly, we did not see finished X-Rays in the case shown at this week’s study group meeting. We have no idea whether the presented case was actually a success, even though it looked beautiful on the day of insertion.

If you found out later that the case wasn’t successful, would you look differently at the treatment that was presented? Would you think twice about adopting that protocol for your patients?

Finished X-Rays and follow-up of at least five years are what I want to see. Are the changes in periodontal bone minimal over time? If so, those patients will get to hold onto their teeth, as those cases can be considered successful. In my opinion any case that is present in the mouth for less than 5 years cannot be used to evaluate the success of a particular technique.

More food for thought: If an instructor advocates for a particular technique, how many case illustrations does he or she offer? One or two cases by themselves are not very convincing and can seem like “anecdotes.” I like to illustrate basic principles with numerous cases, and I show cases that were done according to the same basic principles for over 70 years. I like to show the old cases with the new cases to provide clout that what I am presenting is valid. It is the percentage of cases that are successful that is important in evaluating any technique. I believe strongly that case longevity is the ultimate criteria for success, not case beauty on the day of insertion.

Does the instructor say one thing and do another? Such a scenario is not uncommon. Sometimes there are clues attendees can glean from the presentation. Attendees should look at every presentation with a jaded eye—including ONWARD presentations. Never take the word of the instructor at face value. Always ask questions.

Does the instructor say one thing and do another? Such a scenario is not uncommon. Sometimes there are clues attendees can glean from the presentation. Attendees should look at every presentation with a jaded eye—including ONWARD presentations. Never take the word of the instructor at face value. Always ask questions.

Several take-home questions every attendee should ask are these:

-

How are the techniques shown going to help you in practice?

-

Are you confident that you will have success following the given advice?

-

Would you refer patients to the instructor from what you have seen?

Become the best practitioner in full coverage restorative dentistry that you can be! Don’t settle! Join the ONWARD program and learn how to do crown and bridgework with excellence and confidence, how to save “hopeless” teeth, and how to provide new options for patient treatment that you never thought of. Visit the website and join here: https://theonwardprogram.com/membership/