Some Thoughts on Standards

What is a standard?

A standard is defined as “a level of quality, achievement, or attainment that is considered acceptable or desirable.(1) According to the US dictionary (updated this year), “the word “standard” serves a critical role in defining norms, benchmarks, and measures across various domains, including education, industry, and communication. Its versatility allows for use as both a noun and an adjective, making it an integral part of discussions about quality, conformity, and values.”

Standards are usually specified in documents—both digital and physical. They are guidelines designed to accomplish the following goals:

1. Assure quality

2. Enhance safety and confidence

3. Ensure uniform consistency for benchmark comparisons and interoperability

4. Foster innovation

5. Adapt to new technology or changing needs.

Why are standards important?

Standards assist in determining the best protocol for a particular task. According to Health Standards Organization, the adoption of standards creates widespread impact. High-quality standards are “people-centered, evidence-informed, relevant, and responsive to current and future needs.”(2)

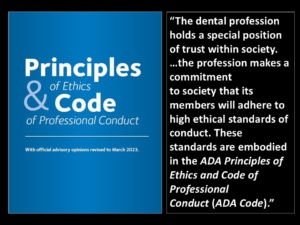

Standards are embodied in the very definition of professional. The achievement of certain standards in the form of a degree allows an individual to become a dental professional. However, the achievement of a degree is just the beginning. Professionals are expected to maintain high standards of ethical conduct, skillful performance, and continuing education throughout their careers. Members of the ADA agree to maintain the standards outlined in the ADA’s Principles of Ethics and Code of Professional Conduct.(3)” Adhering to standards should be “black-and-white,” but often there are areas of gray.

Standards are embodied in the very definition of professional. The achievement of certain standards in the form of a degree allows an individual to become a dental professional. However, the achievement of a degree is just the beginning. Professionals are expected to maintain high standards of ethical conduct, skillful performance, and continuing education throughout their careers. Members of the ADA agree to maintain the standards outlined in the ADA’s Principles of Ethics and Code of Professional Conduct.(3)” Adhering to standards should be “black-and-white,” but often there are areas of gray.

What is the “Standard of Care?”

The “Standard of Care” lies in one of those gray areas. According to Joseph Graskemper DDS, JD, the standard of care has a vague definition that might include these elements:

The “Standard of Care” lies in one of those gray areas. According to Joseph Graskemper DDS, JD, the standard of care has a vague definition that might include these elements:

a. What the normal, average dentist does;

b. What the dentist was taught in dental school;

c. What is taught in dental schools now;

d. The best he or she can do under the circumstances;

e. What the majority of dentists are doing in their practices;

f. What the specialist would do under the same circumstances

Perhaps the best definition of “standard of care” was best stated in Blair v. Eblen: “[A dentist is] under a duty to use that degree of care and skill which is expected of a reasonably competent [dentist] acting in the same or similar circumstances.(4)” The standard is not the highest possible level of care, but it is a level below which practitioners must not sink. Standards are not static, but changes with advances in research, new technologies and educational curricula. One would think that standards are continually rising—with all the advancements in technology– but such is not always the case. In many ways standards have sunk to new lows in some areas of dentistry.

Nevertheless, dental practitioners are expected to continually raise the standard of care that they provide. This endeavor can only be achieved through the pursuit of continuing education and the diligent application of basic principles. Section 2A of the ADA’s Code of Ethics states:

“The privilege of dentists to be accorded professional status rests primarily in the

knowledge, skill and experience with which they serve their patients and society. All

dentists, therefore, have the obligation of keeping their knowledge and skill current.(5)”

Standards for Educational Presentations

Unfortunately, continuing education standards also lie in a gray zone. There do not seem to be clearly defined guidelines for scientific presentations in either CERP or PACE. Both accrediting agencies require conflict-of-interest disclosure, adherence to HIPPA rules for patient protection, and disclosure that images are not falsely manipulated. Aside from these requirements, there do not appear to be any restrictions or expectations. These are some areas that I believe should be addressed by continuing education venues:

Unfortunately, continuing education standards also lie in a gray zone. There do not seem to be clearly defined guidelines for scientific presentations in either CERP or PACE. Both accrediting agencies require conflict-of-interest disclosure, adherence to HIPPA rules for patient protection, and disclosure that images are not falsely manipulated. Aside from these requirements, there do not appear to be any restrictions or expectations. These are some areas that I believe should be addressed by continuing education venues:

1. Conflict of Interest: While conflicts of interest are almost always disclosed, there are boundaries that should be set as to what constitutes education and what constitutes promotion of a particular product. I recently attended a presentation that featured a company logo on every single slide, and it was impossible to determine which cases belonged to the practitioner and which cases came from the company. When I gave a presentation to ADA Annual Session many years ago, every one of my PowerPoint slides was examined before I was allowed to give the presentation. I would never have been allowed to give a presentation with product promotion on every slide, even with prior disclosure.

2. Case Presentations: There is no standard procedure for case presentations. I think a full series of X-Rays should be a required standard for the presentation of any case. It is impossible to judge whether a treatment was justified from a single film or even films for an entire quadrant. What is treated on one side of an arch has profound implications for treatment on the opposite side of an arch. It is my observation that today’s dentists have been trained to think in a piecemeal way. A piecemeal approach focusses on filling a hole or a space. By contrast, an overall approach considers overall health and the prevention of future problems with contingency plans.

3. Treatment Rationale: There are many scientific presentations that feature cases clearly violating basic principles of engineering. This scenario is particularly common with implant treatments. It is not uncommon to see all-on-four implant cases with large superstructures that rest on fixtures that provide inadequate support. Often these superstructures, which are designed to replace missing gingiva and bone as well as teeth, do not allow for basic hygiene both in-office and at home. Dr. Carl Misch, an expert on implant biomechanics railed against overloading implant fixtures and he compiled a great deal of evidence on the biomechanical principles required for successful implant therapy.(6) Dentistry should be corrective as well as esthetic tooth coverings. Presented cases should be based on principles with a proven track record for success.

4. Case Follow-up: Very few presentations include follow-up to demonstrate that the treatments actually work. Most of the time attendees are only shown the esthetic result on the day of insertion. A full series of post insertion X-Rays is almost never shown. Of course, most cases are highly esthetic! But what good is an esthetic result if the case does not hold up or if the patient is not comfortable? Any treatment that does not last at least five years should be considered a failure. Therefore, at least 5 years of demonstrated follow-up should be required in case presentations. The follow-up X-Rays should be compared to the immediate post-op X-Rays to document that no changes have occurred during that time frame.

Standards for Publications

There are specific requirements that are outlined for articles of every type in dental publication. Most have the basic requirement of originality (no plagiarism), fair use of images, and honest presentation of data. Scientific journals have guidelines for the presentation of case reports, research findings and conclusions, and retrospective analyses of literature studies. Most scientific articles are peer-reviewed in an attempt to ensure that the articles are evidence-based with sound conclusions and that the articles will intrigue readers. I have been a reviewer for the Journal of Oral Implantology for many years and I have reviewed over 70 papers. Here are some of my observations:

1. Articles are agenda-driven: There is always a reason why an article was written. Articles that come from corporate or educational insttitutions set out to prove the premise they want to promote. It is very easy to manipulate data to prove that premise. There is very little research that is actually being done for the sake of science. Follow the money!

2. Poor Follow-up: A lot of papers come from Europe because doctoral candidates in Europe have to be published authors in order to receive their doctorates. This requirement is a bad idea. When undergraduates undertake research projects, they are not around long enough to compile at least five years of data. Therefore, most of the time doctoral candidates are unable to form any meaningful conclusions from their research. The only good articles coming from this group seem to be retrospective analyses of previously published studies, and some of those articles are excellent.

3. Complicated Academics: There is a tendency for authors to use language that even the average dental reader cannot understand. It is common for authors to demonstrate their erudite prowess by spewing out research equipment and protocols without explanation. It is assumed that professionals will understand, but in reality the average practitioner has no clue what they are talking about. In such cases, the reader will probably move with alacrity to the next article. Albert Einstein once said, “If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it well enough.” Authors also tend to compile extensive bibliographies as evidence of how many hours they spent researching the provisions for their articles. I know what is involved in writing scientific papers. I wrote a textbook, and I am in the process of writing a second textbook. It is a painstaking process to compile a bibliography of references. But bibliographies cannot make up for flaws in content, so I am not impressed. What impresses me? Content that can actually be learned and applied!

I am currently Vice-President of the American Academy of Dental Editors and Journalists (AADEJ). The Academy outlines general standards for dental publications on its website, in its “Code for Dental Editors.(7)” The code specifies standards for each of four categories:

1. Responsibilities to the readers.

2. Responsibilities to the authors.

3. Responsibilities to the publishing organization.

4. Responsibilities to the community of editors.

Without standards, the reputations of these entities could be irreparably damaged.

How will Standards for Dental Practice change with AI?

Now, standards are great, but they can never etched in stone. All standards should be considered as “works in progress.” Now comes the monkey wrench: AI!

Now, standards are great, but they can never etched in stone. All standards should be considered as “works in progress.” Now comes the monkey wrench: AI!

The use of AI will affect almost every facet of dentistry and standards for the use of AI are essential. AI should be regarded as a tool and never as the final word for any type of use. In a recent article in Futurism magazine, Frank Landymore noted that the “new and improved crop of AI chatbots” are actually “less trustworthy than their forebears, because they’re more likely to make up facts rather than avoiding or turning down questions they can’t answer.(8)”

I am Chairman of Prosthodontics for the Dental AI Association (DAIA), and it is my hope that the DAIA will be actively involved in setting the standards for the use of AI in dental practice. It is abundantly clear that if the profession does not control how AI is applied to Dentistry, AI will become a dangerous tool likely to do harm. It is important that dental practitioners set the rules and control the use of AI for dental practice—and not corporations whose sole motivation is the bottom line. AI will be used in the front office, in the imaging room, in the treatment planning room and in the operating room. It cannot be allowed to pull data from untrusted sources on the internet.

For example, I can envision how AI could be configured to effectively assist dental practitioners in treatment planning, It is currently being used in this way in Medicine. Time Magazine created a special issue last year devoted to AI. In that issue, Dr. Eric Topol, a practicing cardiologist at the Scripps Clinic, told the story of a lady who went to seven neurologists and all seven diagnosed her with “Long Covid.” The treatments for “Long Covid” did not help her. Her sister plugged her symptoms into ChatGPT and AI came up with a diagnosis of “Limbic Encephalitis.” She was treated for that illness and cured. It is easy to see how AI could be a very useful tool to aid medical practitioners.(9)

However, dentistry is different from medicine. ChatGPT is not likely to come up with the right answers for dental treatment options from scouring the internet. Treatment options exist that most dental practitioners know nothing about. Patients commonly receive highly invasive treatments for this reason. Implant therapy, for example, is over-used and used inappropriately for cases where options exist that can save the existing dentition. The failure rate for implant therapies is skyrocketing.

If AI is to be a useful tool for dental treatment planning, it will have to be programmed to inform dental practitioners about treatment options that would never occur to them. It will also have to direct them to receive appropriate training so that they can successfully incorporate those treatment options.

Standards for the Use of AI in Dental Publications

Last month, the American Academy of Dental Editors and Journalists (AADEJ), under the direction of President Chris Smiley, outlined the standards for the use of AI in dental publications in a ground-breaking webinar. Dr. Smiley emphasized that Dental publications “significantly influence clinical practice and care outcomes.” He noted that the unchecked use of Generative AI (GenAI) for the creation of publications “risks introducing inaccurate or misleading information, which could negatively impact patient care.” Therefore, clear guidance for authors and publishers on the responsible use of GenAI in the creation of professional literature is essential. Dr. Smiley outlined standards that writers, editors and peer reviewers should consider when using GenAI in dental publications. These guidelines are available in a white paper handout from the webinar at the AADEJ.(10)

Last month, the American Academy of Dental Editors and Journalists (AADEJ), under the direction of President Chris Smiley, outlined the standards for the use of AI in dental publications in a ground-breaking webinar. Dr. Smiley emphasized that Dental publications “significantly influence clinical practice and care outcomes.” He noted that the unchecked use of Generative AI (GenAI) for the creation of publications “risks introducing inaccurate or misleading information, which could negatively impact patient care.” Therefore, clear guidance for authors and publishers on the responsible use of GenAI in the creation of professional literature is essential. Dr. Smiley outlined standards that writers, editors and peer reviewers should consider when using GenAI in dental publications. These guidelines are available in a white paper handout from the webinar at the AADEJ.(10)

Standard Conclusions

It is obvious to anyone who has lived more than a generation that the standards in every aspect of our society continue to seek out new lows. Low standards are contributing to the decay and stagnation in many aspects of the dental profession and in dental practice. High standards are needed to “turn this ship around. ” Leadership expert Tom Peters emphasizes that “setting a high standard is essential to innovative growth.”

It is obvious to anyone who has lived more than a generation that the standards in every aspect of our society continue to seek out new lows. Low standards are contributing to the decay and stagnation in many aspects of the dental profession and in dental practice. High standards are needed to “turn this ship around. ” Leadership expert Tom Peters emphasizes that “setting a high standard is essential to innovative growth.”

Good leadership for any organization begins with setting high standards. I cannot think of any organization that I have been involved with that did not aspire to lofty goals. High standards inspire members to “outperform.”

Dental professionals have a special responsibility to become leaders of their dental team, of the dental profession, and of the community at large. Leaders have a duty to serve as role models to inspire others. Ray Krok is known for building the McDonald’s fast-food empire. That empire could not have been built without extraordinary leadership. He once commented that “the quality of a leader is reflected in the standards they set for themselves.”

Clearly setting standards begins with you. Raise the bar high for the standards that you set for yourself. My father and mentor, Dr. Elliot Feinberg, always said that one of the hardest commitments for any dental professional is to “be your own worst critic.” No one is looking over your shoulder to grade you on what you are doing. Where will you draw the line of what you will accept?

Remember that your reputation depends not only on what you say, but on what you do. It will be obvious to those around you if what you say does not match what you do. Strive to be respected as someone of high quality, integrity and ethics. Aspire to better yourself through education and practice. Take responsibility for your mistakes and learn to view them as learning opportunities.

“If you don’t set your standards high,” concludes Gordon Lightfoot, “you will never know what you are capable of.”

1https://usdictionary.com/definitions/standard/

2https://healthstandards.org/standards/why-standards-matter/

3 ADA Principles of Ethics and Code of Professional Conduct; https://www.ada.org/about/principles/code-of-ethics

4Graskemper, Joseph P, DDS JD; “The Standard of Care in Dentistry: Where did it come from? How Did it Evolve?” JADA, Vol 135, October 2004; pp. 1449-1455

5ADA Principles of Ethics and Code of Professional Conduct; https://www.ada.org/about/principles/code-of-ethics; p. 5.

6Carl E. Misch, BS, DDS, MDS, PhD (hc); “The Key to Implant Treatment Plans:

Stress Treatment Theorem for Implant Dentistry;” Implant Prosthodontics Monographs; Vol. 1, No. 2; June 2017.

7https://www.aadej.org/resources

8Frank Landymore; “The Most Sophisticated AIs Are Most Likely to Lie, Worrying Research Finds The AIs are “getting better at pretending to be knowledgeable;” Sept 28, 2024; https://futurism.com/sophisticated-ai-likely-lie.

9Pamela Weintraub, “The Future of Medicine;” Time Magazine Special Edition: Artificial Intelligence; Spring 2024; p. 40.

10Smiley, Chris; “Guidance for Authors and Editors on the Use of Generative AI;” [White Paper Webinar Handout] March 20, 2025; For a copy, contact the AADEJ at information@aadej.org.